Imagine you’re living in Paris in the fifteenth century. You have a little extra money set aside. How do you deepen your relationship with God while also publicly showing off your devotion? You want a Book of Hours. Books of Hours were the most common type of personal book in the Middle Ages, owned by clergy and lay people alike. They were compilations of prayers, custom-made for each individual devotee. They had prayers for most occasions and could fit any mood. In short, they were the original mixtape. And just like the tape you replayed for weeks after that break-up, they could be intensely personal.

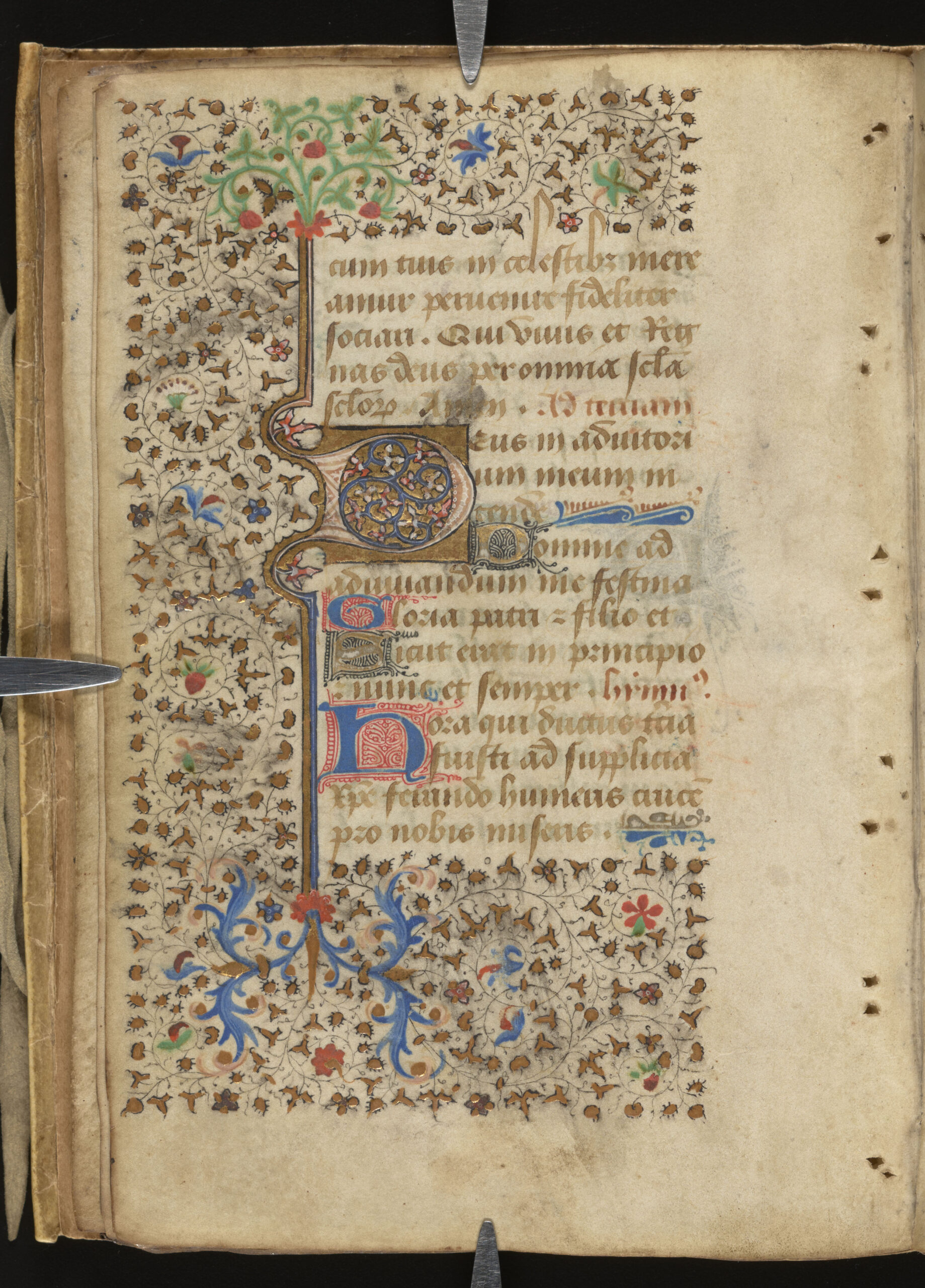

Hargrett Hours, opening of one hour of the Long Office of the Passion, f. 18v

Let’s say you’re commissioning the book we now know as the Hargrett Hours. Depending on how much money you have to spend, you can customize it to reflect your personality and interests. It’s not just size and how much bling you want on the page. What selection of prayers will serve your personal needs? What language(s) do you want it to be in? And what saints do you want to commemorate between its pages? These especially can tell us a lot about you and your relationship to the divine.

Let’s see what you chose.

The Suffrages in the Hargrett Hours

If you’re suffering from some awful ailment or a terrible toothache, or if you’re praying to place first in your upcoming archery tournament, you might need some divine intervention. But you can’t always go straight to the Big Man upstairs. Sometimes, you need the help of an intermediary to plead your case. You need a saint or two. Or maybe thirty-nine. That’s how many saints are in your Book of Hours. You’ve included a grand total of forty-one prayers for the saints, invoking them to intercede on your behalf with God. These are called suffrages.

Each saint has special qualities that set them apart from the rest of humanity: incomparable generosity, unshaken patience, unyielding devotion. Some saints are more popular than others and, like twenty-first-century celebrities, they go in and out of the spotlight (see this blogpost on Saint Fiacre).

Most people would ask for their favorite Apostle, certainly a local confessor or two, and maybe a couple of virgin martyrs. You asked for all of the Apostles, just in case; added an assortment of local Parisian saints, like Germain of Paris and Genevieve; and a whole host of virgin martyrs. You didn’t only pick the most fashionable ladies, like Saint Katherine and Saint Margaret; you also included the more obscure desert-dwelling hermit, Mary the Egyptian. Your tastes are clearly more eclectic.

You also paid special attention to Biblical women, Mary’s inner circle. Her mom, Anne, gets two suffrages in your book, and her two sisters, Mary Jacob and Mary Salome, are also featured. You understand the power of feminine intercession.

The French Prayers

You saved the best for last. Your custom suffrage section concludes with three prayers to the lead Virgin herself, Mary. You asked for two of them to be in French, a bold choice. Latin is the obvious medium for a prayer book. It’s what you hear in church every week. If you are a lay person, you may even sort of understand it. But it is still a foreign language to you.

Da nobis eorum precibus gloriam sempiternam et proficiendo celebrare et celebrando proficere.

Grant us eternal glory through their prayers, and let us worship by doing good and do good by worshiping.

(f. 66v)

Since the saints are universal, it makes sense to communicate with them in the official language of religion. All of the prayers in your book are meant to establish a personal relationship with the saints. But after a couple of dozen suffrages, they all start to sound alike:

The prayers to the Virgin are different. Compare the above, “grant us eternal blah blah blah” to:

en ycelle heure mes yeulx seront si agrevé de la noire obscurté de la mort que je […] ne pourray mouvoir la langue pour prier ne pour toy appeller et mon chétif cuer le foible tremblera angoisseusement pour la paour des anemys d’enfer […] mais te souviengne lors de la prière que je faiz orendroit et reçoy m’âme en ta benoîte garde en ta foy et en ta deffense

in that hour my eyes will be so clouded by the darkness of death, that I will not […] be able to move my tongue to pray or call you, and my pitiful, weak heart will tremble anxiously in fear of the enemies from hell […] remember this prayer I say now, and receive my soul into your blessed charge, your faith, your protection

(ff. 84r-84v)

Do you hear the difference? The saints intercede on behalf of mankind, so we invoke them collectively. But when you’re haunted by your personal demons, scared of the dark, you want your Mother. This is between you, as an individual, and her, and you want to make sure you can understand and pronounce every word you say to her. There’s no surer way to get it right than in your mother tongue.

Where Are You in the Book?

This book is one of your most prized possessions, one that is entirely unique to you. Sometimes they became precious heirlooms. You would be justified in wanting it to feel like it was really written for you. Some wealthy patrons may have commissioned a miniaturist to draw them into their books. Other less extravagant ways to personalize a book included simply having your name written into it. As far as we can tell from what’s left of your book, you did not go to any of this trouble.

But you did make an interesting choice. You may have cared that the prayers you were reciting for God’s ears sounded like you. We think you tried to choose a voice that matched your gender.

Unlike English, French and Latin words are gendered. In Latin, many nouns and adjectives have different endings when they are masculine and when they are feminine. So in a sentence like “peccator sum” (“I am a sinner”), the sinner is a man, but in “peccatrix sum,”, the sinner is a woman.

Why does this matter? Well, many texts used the masculine as the default. If you were a woman, you would have just known to adapt and correct the ending while you were reading. But maybe you were like some women who wanted the text to be written with them in mind. So you could have asked the scribe to feminize it for you. There was one place in the Hargrett Hours where we think you might have done just that.

Hargrett Hours, from the prayer to the Guardian Angel showing the feminine participle “educta,”, f. 60v

In your prayer for your Guardian Angel, you pray to God: “when I am led from this body to you, do not send harmful spirits down to terrify or trick me” – a pretty reasonable request! In the original Latin, the word for “led from” is “educta”, (with a feminine -a ending). That must mean you were a woman, right? Well, maybe.

In the same prayer, there are two other places where the word endings are masculine and imply a masculine reader. So which is it?

Curiously, the section of the book that has the feminine ending is written by a different scribe. It happened sometimes that a scribe would take over copying the text from their colleague (scribes needed breaks, too). Notice the handwriting changing from the page on the left to the page on the right?

Hargrett Hours, opening of the prayer to the Guardian Angel where the change of scribal hand is evident, f. 59v-60r

The main scribe took over again on the next leaf, but the person filling in briefly switched this prayer to the feminine voice. Why would they do that? What does this mean for you?

The Hargrett Hours is a nice book, but let’s be honest: you did not spend top dollar on it. Your book would have still cost a pretty penny, but the production quality is not top tier [link to the Artz Hours blog post]. Scribes making Books of Hours were (probably) not just making up prayers as they went, but were instead copying from various older texts to make their patron a custom collection. Often these books were “cobbled together” from other sources.

So one explanation may be that the filler-scribe was copying from his own version of the prayer, one which was originally prepared for a female customer. If that is true, the Hargrett Hours points back to a female customer somewhere in the book’s lineage, which is exciting. If you have paid a few more silver coins, you might have had a book with consistent grammar, written by the same scribe all the way through. You might have even had a more professional scribe who would have dedicated all of his time to curating the perfect book for you. But where would the fun be in that? That would have been too easy for us.

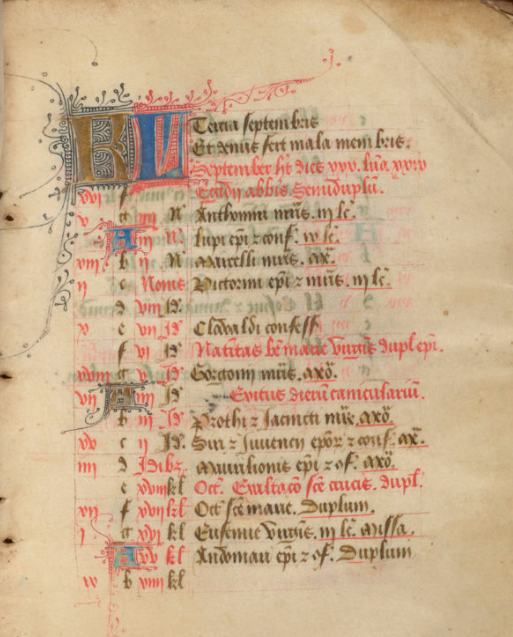

We tried to match the handwriting, and it turns out, the same scribe who took over may have also written the calendar of your book, one of the most mysterious pieces of the puzzle. Your calendar features a unique, and frankly baffling, assortment of saints and feast days. So it may be that the main scribe was just filling in an order, but Calendar Scribe must have known you. In order to come up with such a weird patchwork of a calendar for you, you must have had a consultation with him. Did he know you were a woman, and that’s why he used the feminine ending in folio 60v?

Hargrett Hours, September page in the Calendar, f. 9r

Maybe you weren’t commissioning the book for yourself at all, but for a friend. And somewhere the scribes’ wires got crossed. Even though we would love to know you, we can’t entirely solve your mystery with the few clues you’ve left us. But we think you could have been a woman.

Maybe you just weren’t that particular, and a few masculine endings did not bother you. After all, if you knew just a little bit of Latin from church, it wouldn’t have been too hard for you to change the gender of words to match how you were feeling that day. If you didn’t know much Latin, then it wouldn’t have made a difference anyway. God and the saints would understand.

By Mounawar Abbouchi and Zack Dow

for Team Suffrages 4.0 (Grace Deaton, Kristina Durkin, Rachel Menikoff, and Anya Ricketson)

References

Dunn-Lardeau, Brenda. “Les suffrages aux saints dans les livres d’heures: Entre choix personnels et marques d’appartenance à une société.” Le texte médiéval dans le processus de communication, Classiques Garnier, 2019, pp.375-391.

Duffy, Eamon. “A Very Personal Possession.” History Today, November 2008, pp. 12-18.

Reinburg, Virginia. “‘For the Use of Women’: Women and Books of Hours”. Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal, vol. 4, 2009, pp. 235-240.

Reinburg, Virginia. French Books of Hours: Making an Archive of Prayers, c. 1400-1600. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Rudy, Kathryn M. Piety in Pieces: How Medieval Readers Customized their Manuscripts, Open Book Publishers, 2017.