As the precinct delves further into the enigmatic Hargrett Hours investigation, we detectives of Squad Calendar have a hunch. Here’s what we know: the object of interest is a medieval manuscript called the Hargrett Hours that dates to the 15th century. It’s a Book of Hours, which is a kind of prayer manuscript intended for personal devotional prayer. Most Books of Hours include a calendar indicating when to celebrate certain feast days and saints. Those specific dates usually clue you into where a Book of Hours was intended to be used, AKA its “use.” The Hargrett Use Case seemed closed when retired detectives who originally investigated this book solved the case, claiming it was use of St. Chapelle or Paris. Our current investigation raises suspicions that St. Chapelle might be a red herring. Squad Calendar has narrowed down the possible perps by focusing on what characterizes certain uses and how the Hargrett Hours compares.

The reason we reopened the Hargrett Use Case was because of inconsistencies we found when comparing Hargrett’s calendar to other calendars. First, some background information is necessary to understand said inconsistencies. “Use” refers to the specific location where a manuscript is intended to be used. This could be a country, city, or church. The different sections of a manuscript can help specify the “use,” and that’s especially true for calendars at the beginning of Books of Hours. The calendar in a book of hours has listed feast days and saints that are commonly observed in a specific country, city, or church can indicate its “use” (Plummer 149).

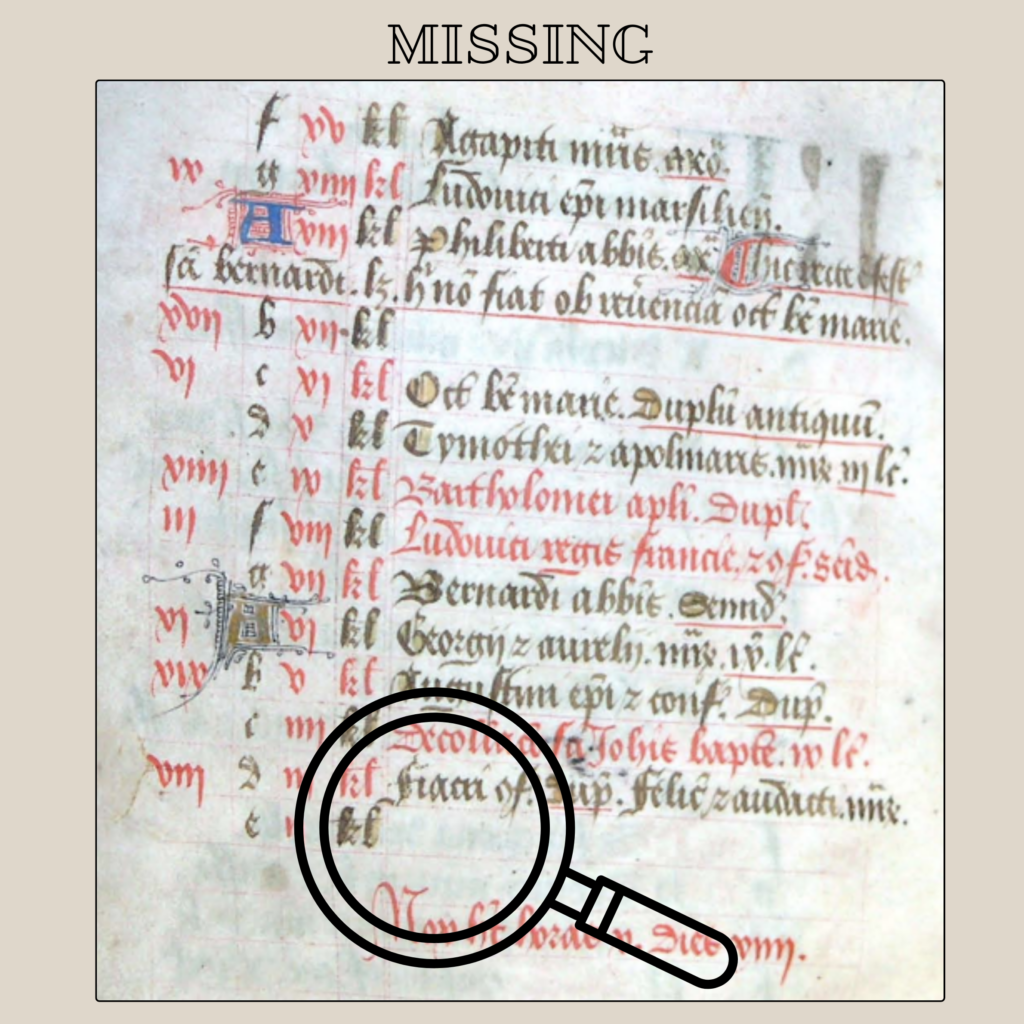

Books of Hours usually have calendars filled with much more than liturgical manuscripts. Calendars appear in many kinds of manuscripts, but especially books that are intended for liturgical use. Liturgical manuscripts are meant for public services in a church, but books of hours are not. However, while Hargrett is a Book of Hours, it maintains a much emptier calendar, which is characteristic of liturgical manuscripts (150). The fact that Hargrett is a Book of Hours but is emptier like liturgical calendars makes finding a clean-cut “use” for the Hargrett Hours more challenging. Our perp is all the more difficult to catch.

We then decided to see if our suspicions led to anything. We investigated the saints and feast days of the Hargrett calendar to see if the dates lined up with what a typical St. Chapelle calendar would have. Using Corpus Kalendarium (CoKL, Aaron Macks), a database of calendars from European Books of Hours, we found three dates of interest:

1. August 11th, the Feast of the Crown of Thorns, appeared in over 37 manuscripts in the CoKL database.

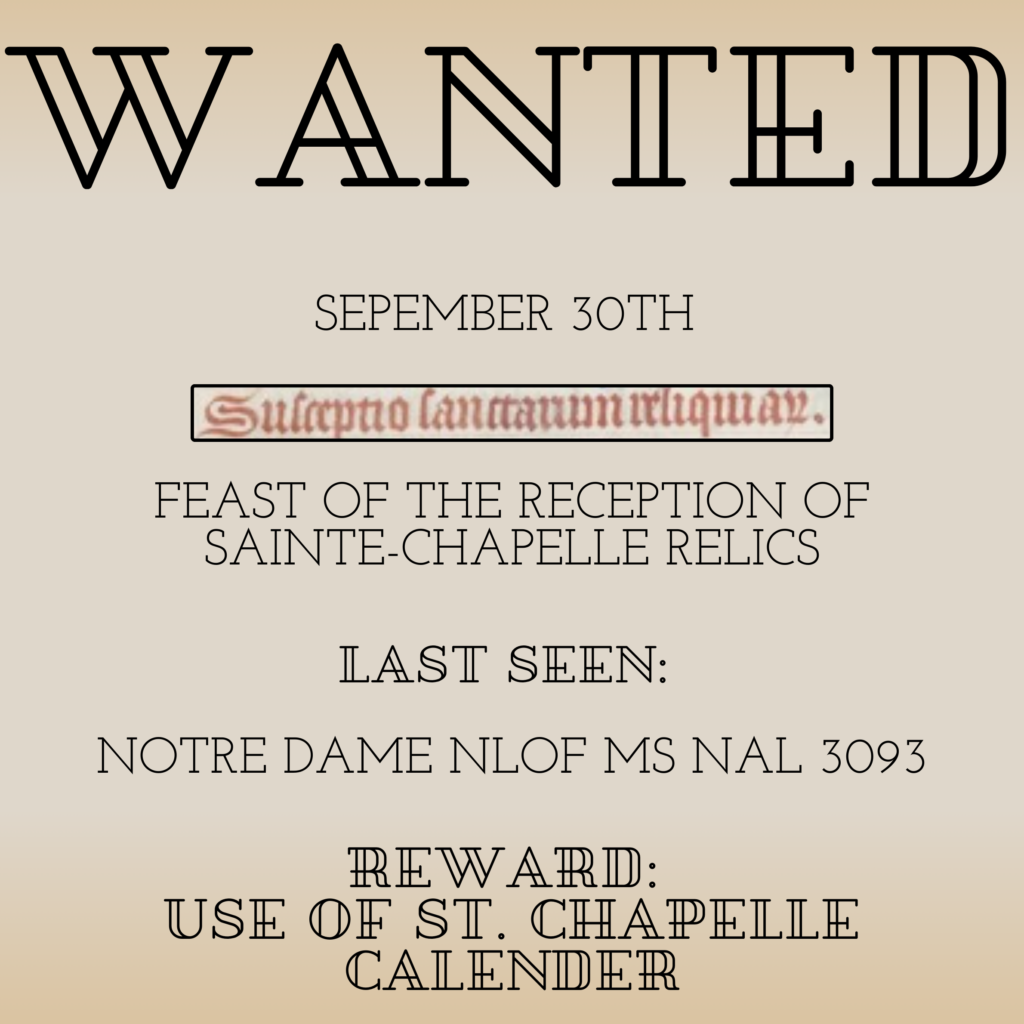

2. September 30th, the Feast of the Reception of Sainte-Chapelle Relics, appeared in only three manuscripts from our data pool. This feast day is an extremely important feast day pertaining to relics at St. Chapelle.

3. The rarest date we have listed is December 4th, the Reception of Notre-Dame Relics, which indicates Notre Dame as a possible “use.” CoKL had only one other manuscript with this date.

4. April 26th is another important feast date that the Hargrett Hours does contain. April 26th is the day of the Dedication of the “chapel of paris”, and the presence of it in the Hargrett Hours is an indication that the Hargrett Hours could be a use of Ste-Chapelle.

Hargrett contains the August 11th and December 4th feast days, but not September 30th’s feast day. First, we delved into the missing feast day: the Feast of Reception of St. Chapelle Relics. How could Hargrett be a St. Chapelle use but not include a feast day directly related to St. Chapelle? After further investigation, an article was discovered that shed some light on two of these dates. Robert Brenner states that without the September 30th date – an extremely important feast day for Ste. Chapelle – a manuscript is likely not a use of Ste. Chapelle at all, and may instead belong to the Capella Regis (19).Then what makes a Capella Regis manuscript? The September 30th date marks a calendar as either St. Chapelle or Capella Regis, says Brenner (19). We deduced from Brenner’s takeaway that the perpetrator couldn’t be St. Chapelle because it’s missing the vital September 30th date… or can it still be use of St. Chapelle?

Things get complicated due to regional disconnect and desire for a Christian canon. A manuscript’s “use” does not tell us where the manuscript was originally made, and the mystery of where they were made can mean a manuscript can have multiple “uses”. A lot of French manuscripts like Hargrett have their “use” attributed to larger cities such as Paris; however, they were often made in provincial areas (Plummer 149). Sometimes, they weren’t written in France at all, but in the 15th century region of Francia, AKA modern-day Belgium (Bouchard 13). This disconnect between where French manuscripts were written and the intended location could mean calendars have some anomalous characteristics when compared to what the standard was for “uses” of a particular location; the standards can get muddied by this geographic distance. Such geographic distance could signal why a Book of Hours can seem to be both use of Paris and use of Ste-Chapelle simultaneously. For Hargrett, this means it could be more than one “use”. Another complication is the aspect of trends or the desire for a Christian canon. During the 15th century, Books of Hours were increasingly written according to the use of Rome which conceals both the origin of the manuscript and its intended place of “use” (Plummer 150). Hargrett remains a tough nut to crack.

Taking the muddied waters of “use” into consideration, the anomalous date of the Reception of the Relics of Notre Dame (December 4th) raises the question: could Hargrett be use of Notre Dame? Squad Calendar compared Hargrett to a Missal of Notre Dame, MS Lat 622 (Paris), to find answers. Though the calendar is a key feature, we cross-examined Hargrett with Squad St. Chapelle to uncover any more potential useful liturgical clues. We found that a Missal is different from a Book of Hours because it is used directly in church service, usually by someone in the clergy, instead of being a book for personal devotion. A Missal contains the correct plan of service for each feast or saint’s day because the plan of service varies for each feast. The calendar signals which service for a certain saint is going to be said on that specific day. Despite the calendar variations between Missal MS Lat 622 and Hargrett Book of Hours, many similarities arose between MS Lat 622 and Hargrett Hours. These similarities provided us with visual clues to what dates are more important than others.

The most important dates in the Notre Dame Missal are marked through the appearance of the written text and the grading at the end of a calendar entry. Golden (or illuminated) lettering for saints and feast days in the calendar show those days are most important to whoever is utilizing the calendar. Grading serves a similar purpose to the gold lettering, as it refers to latin phrases that punctuate the end of an entry on a medieval calendar. The order of the liturgy is affected by the day, rank, and season, and this is also associated with the grading. In Hargrett and other calendars, the phrases annum festum, duplum, and semiduplum are phrases that mark the most important entries, so looking at those entries is vital to understanding what the “use” is. This grading and its consistency are key to solving the freshly reopened Hargrett Use Case. Our investigation will continue down this path by comparing more of the grading and visual clues of different Notre Dame calendars. If we find the grading lines up with that of the Hargrett Hours, we have a hit!

We hope the precinct takes our investigation into consideration and we get more manpower to find the answer: Is Hargrett really use of St. Chapelle? Or is it Notre Dame, Capella Regis, or something else? Could it be a mashup of “uses”? There are still many questions to be answered, too many for Squad Calendar to uncover this fall. We’re focusing on figuring out how similar the grading is between Hargrett and other Notre Dame calendars because of that pesky December 4th date in Hargrett. However, that still leaves comparing Hargrett’s calendar with other “uses,” and going through this same process with the anomalous August 11th date. Can you help solve this case?

References

Bouchard, Constance Brittain. Rewriting Saints and Ancestors: Memory and Forgetting in France, 5-12 The Middle Ages Series. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014.

Branner, Robert. “The Sainte-Chapelle and the Capella Regis in the Thirteenth Century.” Gesta, vol. 10, no. 1, 1971, pp. 19–22. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/766564. Accessed 5 Dec. 2023.

Hargrett Hours: Athens, GA, UGA, Hargrett Library, MS 836, https://hargretthours.ugamedieval.com/calendar/. Accessed 06 December 2023.

Plummer, John. “Use and Beyond Use.” TIME SANCTIFIED – The Book of Hours in Medieval Art and Life, edited by Roger S. Wieck George Braziller. Inc., NewYork, 1988, pp. 149-156.

Wieck, Robert S. The Medieval Calendar. Locating Time in the Middle Ages. The Morgan Library and Museum, New York, 2017.