(This post originally appeared on the “Hargrett Hours Project” Blog. Find Original Post Here)

If there’s one thing that most people who write on medieval Books of Hours can agree upon, it’s that Books of Hours need to include a certain set of features. The all-important feature being the Hours of Virgin. The Metropolitan Museum of Art calls it “the heart of any Book of Hours”, echoing almost the exact wording of Roger Wieck in Time Sanctified (Wieck 60). The Hypertext Book of Hours calls the Hours of Virgin the “text that defines” a Book of Hours. Virginia Reinburg even goes so far to claim “The hours of the Virgin was the central text of the Book of Hours” (Reinburg 209). Imagine my surprise, then, when I began researching Baltimore, Walters Art Library MS W.164 only to realize, guess what, that heart or central component of the text was nowhere to be found. And it wasn’t even missing from the text, a quire that had been lost. No, the Hours of the Virgin never existed in MS W.164.

60r -Deposition. “Christ Coming Down from the Cross”

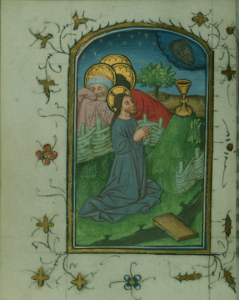

Besides this weird and kind of important missing feature that changes everything about the book, MS W.164 is actually pretty normal. Produced around 1430 (which will come up later), the manuscript has a calendar, prayer to God the father, an Office of the Dead, and a pretty long sequence of suffrages. So far, so good. But right in the middle, beginning on 15v, where one would expect a cycle of prayers to Mary, we get a full page miniature depicting “Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane”, beginning a sequence of liturgical hours that extends the much more common Hours of the Cross.

15v – “Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane”

Now, the inclusion of the Hours of the Passion is interesting but common enough not to be completely strange, as a number of manuscripts include both the Virgin and the Short Hours of the Passion, including the British Library’s MS Add. 50001 and MS Add. 18852. What is strange, however, is the replacement of the Hours of the Virgin with the Long Hours of the Passion. MS W.164 is not alone in this either, as Walters MS W.441 also includes the Long Hours of the Passion, in addition to UGA’s very own Hargrett Hours.

So, the two most obvious questions would be: Is this even a Book of Hours and why would someone want the Passion over the Hours of the Virgin? One is a bit easier to answer than the other. Tackling the first question really depends on what accepted definition of a Book of Hours we want to listen to. If we take Wieck, Reinburg, and MMOA at their word, then the two texts probably fall under the category of “prayer book” which is also what the Digitized Walters Manuscripts calls W.164. Oddly, in fact, Wieck does include MS W.164 in Time Sanctified, but he doesn’t actually comment on its uniqueness (Wieck 209). Jessica Brantley even claims that “any book that contains the Hours of the Virgin may be considered to belong to the genre [of Book of Hours], regardless of what else it might contain” (Brantley 61).

However, if we want to broaden that definition, both the Hargrett MS 836 and MS W.164 include a sequence of hours for devotional prayer, making them, technically, Books of Hours. In MS W.164, the Long Hours of the Passion, in fact, takes the formal place of the Hours of the Virgin, following the calendar. Further, the highest level of decoration, and inclusion of full-page miniatures preceding each hour suggests the Hours of the Passion as the central piece of MS W. 164. Along these lines, MS W.164 fulfills every generic expectation, including having a prolonged sequence of devotional prayers. The simple fact that those prayers are of a different order should not limit their inclusion into the genre.

Question two, the why question, is a bit more difficult to answer, as there are a number of factors at play and we can only hazard a generalized guess at the reasoning. Remember how we were going to come back to the year in which MS 164 was produced? Well 1430-1440, broadly fits its into the “new level of significance” that the passion was accorded during the late Middle Ages (Schlusemann ix). In fact, devotion to Christ’s Passion saw something of a resurgence during this period as “Passion devotion … was in fact one of the most important influences impinging on the culture of the later Middle Ages” (Schlusemann ix). Defining the late Middle Ages as the 1400s, this influence can also be seen by the fetishization of “the late medieval arma Christi”, which collected the objects of Christ’s Passion (Cooper 2). It stands to reason that this movement would also influence liturgical texts. Walters MS W.164’s abstract even assumes, “The original owner had a strong interest in the passion [that] is evident in both the choice of texts and images.” Obviously, this trend did not impact a majority of Books of Hours produced during the time, but the Passion’s influence on all manner of religious materials would, of course, manifest in some creations.

Time period is only one answer to a complex question that varies manuscript to manuscript. The previously mentioned British Library manuscripts include both Hours and were produced roughly around the same time. MS W.441 was, mostly, “made c. 1500, but it had remained unfinished”, suggesting perhaps that its owner had run out of money in it’s creation or even died. Why Walters MS W.164 doesn’t include the Hours of the Virgin may, in fact, relate to how much money it took to produce both Hours in a single manuscript and the editorial decisions that had to be made. While W.164 was completed, unlike W.441, it’s possible that it was originally intended to contain the Hours of the Virgin before budgetary concerns sidetracked that process. Again, we can only guess at its owners original intention.

The inclusion of Passion over Hours of the Virgin relates to both genre and intended audience. The cataloguer’s assumption that the original owner had an interest in the Passion fits into a historical trend that moved away from the cult of the Virgin to the Passion, but it also places it firmly within the genre of a Book of Hours. The liturgical prayers may have had different devotional intentions but, still fit into the broader purpose behind a Book of Hours . Instead of hopeful prayers to the Virgin, reflecting on the Passion emphasized the “suffering humanity” of Christ’s sacrifice (Schlusemann ix).

Works Cited

- Brantley, Jessica. “Forms of the Hours in Late Medieval England.” The Medieval Literary: Beyond Form. ed. Robert K. Meyer and Catherine Sanok. D.S. Brewer, 2018.

- Cooper, Lisa. and Denny-Brown, A. The Arma Christi in Medieval and Early Modern Material Culture. Ashgate, 2014.

- Reinburg, Virginia. French Books of Hours: Making an Archive of Prayer, c.1400-1600. Cambridge UP, 2012.

- Schlusemann, R. M, Bernhard Ridderbos, and A. A. (Alasdair A.) MacDonald. The Broken Body: Passion Devotion In Late-Medieval Culture. Groningen: Egbert Forsten, 1998.

- Wieck, Roger. Time Sanctified: The Book of Hours in Medieval Art and Life. George Braziller, 2001.