(This post originally appeared on the “Hargrett Hours Project” Blog. Find Original Post Here)

The Suffrage group made some good headway establishing the original owner(s) and provenance of the Hargrett Hours Suffrages this semester: the inclusion of local saints like Genevieve pointed to Paris and the Suffrages’ focus on the figures of the Holy Family (Saint Anne, Saints Mary Jacobe [Cleopas] and Mary Salome, and the Virgin Mary) indicate a female owner. What has been more challenging to evaluate is the efficient, almost business like tone of all but the last three prayers and the Suffrages complete lack of miniatures [1]. I’ve come to realize, however, the issue isn’t the text but, rather, my original presumptions about it. I would like to cautiously venture that the Hargrett Hours Suffrages are not affective in nature because they are not supposed to be. The Hargrett Hours may be an example of the efficacious prayer movement, rather than representative of the more common – or at least more commonly expected – affective lay devotion.

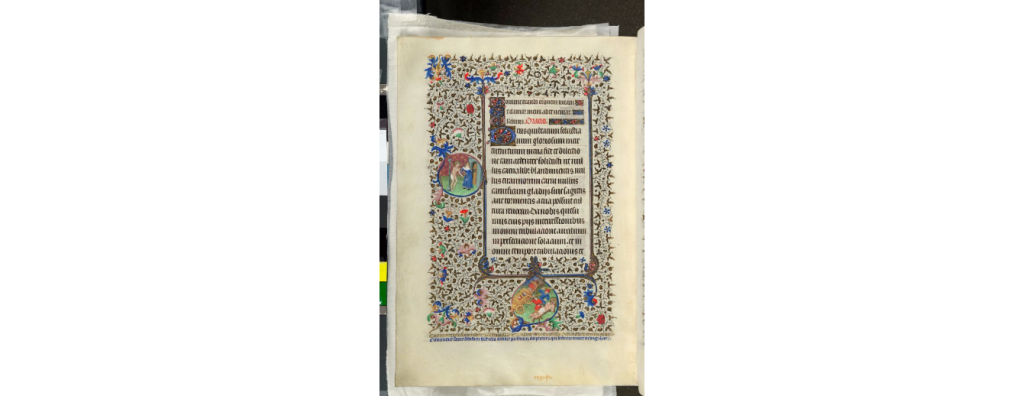

Affective reading and prayer encouraged people to imagine themselves in a biblical scene, like Christ’s Passion or his Nativity, in order to become fully moved and absorbed into their prayer. Many lay people used visuals as an aid for affective practices, such as a glimpse of the host in church or the illuminated miniatures included in a Book of Hours.

Suffrages were usually some of the most illustrated areas in a Book of Hours, and many books included explicit images of martyrs, Christ, and their wounds so that the reader could better visualize and insert themselves into stories of faithful suffering.

As we have it, the Hargrett Hours does not contain any miniatures, which stands in contrast to what we know Books of Hours and their role in prayer. Most of the Suffrages are very generic and their language, while traditional, is not particularly moving or emotional. Although they do include some lovely decoration, there are no images accompanying any of the prayers. The Hargrett Hours are, however, French. While affective piety may have been the standard for lay piety in England, there was another popular movement, called efficacious prayer, in play in France. Like affective piety, efficacious words and prayer had their origins in monastic practice (specifically, Anselm of Canterbury and the Cluniac orders) [2] and, also like affective prayer, became adapted for use by the praying public. Efficacious words or efficacious prayer focuses on the effects devout words (or devoutly said words) can have [3]. Unlike affective piety, which relies on images and passive meditation, efficacious prayer is active. The person praying relies less on pictures of Christ’s wounds than on focusing their prayers on affecting some kind of change.

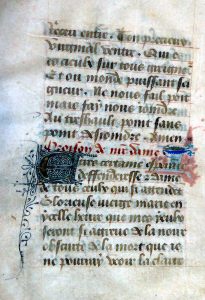

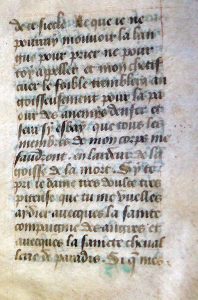

Efficacious prayer was also amenable to the vernacular. One of the most interesting elements in the Hargrett Hours Suffrages are the three vernacular prayers to the Virgin Mary at their conclusion. While some of the earlier prayers contain French rubrics or individual French words, they are predominantly Latinate. The three concluding prayers are all rubricated “Oraison de medame,” or “Prayer to my Lady.”

These prayers are personal and individual; while the Virgin Mary was often styled “Our Lady,” these

prayers – and the reader who decided on their inclusion and perhaps the words – are written in the first person, a marked difference from the previous Suffrages. The first person (“ie” for French “Je”) used in the prayers make them immediate and active. The Virgin, humankind’s heavenly mediator, is an excellent model of efficacy for the woman originally reading the Hargrett Hours attempting to impact her world through her words.

So what, if anything, does this mean for the Hargrett Hours Suffrages? I’m honestly not sure. I do think that if we consider the manuscript within the context of efficacious words and prayer rather than affective piety, the manuscript becomes less of a lower-cost Book of Hours for an upwardly mobile Parisian housewife (an assumption I must admit I worked from for at least the latter third of the semester) than a text designed to help its reader become a more powerful agent of change through their prayer. It could also mean that the manuscript was possibly designed with the semi-professionally religious woman in mind [4], although I do feel that the Suffrages’ emphasis on the Holy Family makes it a more likely a possession in a lay home. It also reminds us that manuscripts are much more than they appear, and what at first looks like nothing more than a mid-range Book of Hours is actually a manuscript that defies easy taxonomy. If the Hargrett Hours are, as I suspect, more closely connected to popular beliefs about efficacy rather than affectiveness, then they also remind us to not let what we already know about medieval texts overly-influence what we’re only coming to know about the Hargrett Hours.

[1] Some of the students researching the Hargrett Hours feel the manuscript may have included some miniatures at some point, and that they were removed or destroyed in the nineteenth century. Others, myself included, are not as convinced, and believe that the current evidence, particularly its folio and line continuity, points to the Hargrett Hours as a Book of Hours which never included miniatures.

[2] Fulton, Rachel. “Praying with Anselm at Admont: A Meditation on Practice.” Speculum, vol. 81, no. 3, 2006, 704.

[3] For further reading on efficacious prayer in medieval France, please see Patrick Henriet’s La parole et la priere au moyen age: Le verbe efficace dans l’hagriographie monastique des XIe et XIIe siécles.

[4] The Calendar group has placed the Hargrett Hours to near or around Sainte-Chappelle: https://ctlsites.uga.edu/hargretthoursproject/discoveries-in-the-hargrett-hours-calendar/.

References

Fulton, Rachel. “Praying with Anselm at Admont: A Meditation on Practice.” Speculum, vol. 81, no. 3, 2006, pp. 700 – 733.

Henriet, Patrick. La parole et la priere au moyen age: Le verbe efficace dans l’hagriographie monastique des XIe et XIIe siécles. De Boek Universitée, 2000.

The Bedford Hours, British Library, ADD MS 18850. http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_18850.http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Add_MS_18850

The Hargrett Hours, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Georgia, MS 836.

The Hours of Mary of Burgundy, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Das_Stundenbuch_der_Maria_von_Burgundhttps://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Das_Stundenbuch_der_Maria_von_Burgund.