Differing Passion Accounts According to John in Books of Hours

Authored by Kristina Going, Katherine Haire, Kara Krewer, and Ceciley Pangburn

The Passion account that appears in the Hargrett Library MS 836 is from the Gospel of John, chapters 18-19. In order to learn more about this Passion account and its inclusion in the Hargrett Hours, we decided to research the various ways that the Passion accounts appear in other Books of Hours. We narrowed our research to books that had been previously identified (in 2017-18) in manuscript descriptions as containing some form of John’s Passion account, because we wanted to compare their similarities and differences to the Hargrett Hours. Roger Wieck, Head of Medieval and Manuscript Studies at the Morgan Library, determines that “the version [of the Passion account] used most frequently is John’s,” making this an optimal starting point (Wieck 104).

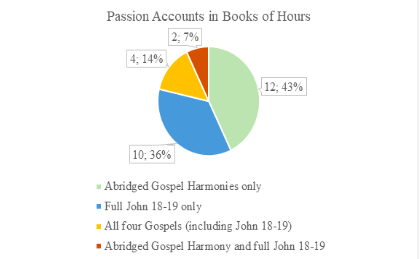

Figure 1: Pie Chart of the Full John and Abridged Accounts

Of the 217 manuscripts in our data pool, only seventy-six contained Passion material; of those, twenty-seven (excluding the Hargrett Hours) had the Passion account according to John and were available in facsimile. It is clear from the limitations of our data pool that the conclusions drawn are, perhaps, not indicative of all Books of Hours containing Passion accounts; but the data does provide us with a good estimation or theorization regarding possible trends.

We researched twenty-eight manuscript facsimiles, including the Hargrett Hours. Twelve of those manuscripts had Passion accounts that had been abridged, with John as a foundational text. The other sixteen included the full John 18-19 Passion (according to the Vulgate) in some form. Of those fifteen, ten had the full John 18-19 Passion only, four had all four Gospels (including John’s), and two had both abridged Gospels and full John 18-19 Passion accounts.

In total, fourteen manuscripts included abridged Passion accounts, and sixteen included full John 18-19 accounts (two of those manuscripts having both). Those are significant numbers on each side, and it suggests that both types of Gospels shared similar popularity.

The Hargrett Hours contains the full John 18-19 Passion account. In researching the abridged accounts and the full John Passion accounts, we began to question why users of Books of Hours (and maybe the Hargrett Hours) decided to commission one version over the other. Working closely with the texts and comparing them to the Latin Vulgate, we determined that the narrative of the abridged Passion contains the highlights of Jesus’ physical ordeal from each of the evangelists while the full account includes an emotionally distressing journey, alongside the physical torture Jesus endures. We also noticed the manuscripts with full John 18-19 accounts had a high likelihood of being very personalized.

Abridged and Full Passion Accounts

In our research, we noticed the abridged accounts were not simply abridged John passages. They also included verses here and there from the three other Gospels: Matthew, Mark, and Luke. These passages were what we came to learn were called Gospel Harmonies. Maureen Boulton explains them best, as when “elements from all four Gospels are woven together, and any particular incident contains details from each Evangelist” (Boulton 35). This trend is frequently seen in narrative accounts of the Passion, where they simply draw from all four Gospels or work from an existing Gospel harmony source. The Gospel Harmonies in the particular manuscripts we studied use John as a foundation and add details from other Gospels to create a more comprehensive account.

Interestingly, the Gospel Harmonies only appear in Books of Hours in their abridged version. The abridged account does something very unusual and unexpected for a Book of Hours; it removes all mentions of Mary and mostly focuses on the physical torment endured by Christ on the Cross. They also include the miracles which occur upon Christ’s death, as they appear in Matthew 27 and Luke 23:45.

| Verse | Summary |

| John 19:1-3 | Christ is flogged, receives the Crown of Thorns and purple robe, and is beaten and ridiculed. |

| Matthew 27:30 | Christ is spit on and beaten. |

| John 19:16b-18 | Christ is taken to Golgotha and crucified with two criminals. |

| John 19:28-30 | Christ is given sour wine to drink from a sponge, after which he bows his head and passes away. |

| Matthew 27:51-52 | Series of miracles (some concurrent with Luke): the temple veil tears in two, earthquake, and the dead are raised. |

| Luke 23:45 | Series of miracles (some concurrent with Matthew): solar eclipse and the temple veil tears in two. |

| Matthew 27:54; Mark 15:39 | The centurion sees the miracles and believes that He was the Son of God. |

| John 19:34-35 | The soldier pierces Christ’s side; blood and water flow out of the wound; those who saw it believed that Christ was telling the truth. |

Figure 2: Most common way of Abridging John’s Passion account; referred to as abridged Gospel harmonies.

The removal of the Virgin Mary is peculiar because Books of Hours are devoted to Mary; the defining text in Books of Hours are the Hours of the Virgin (Weick 60; Reinburg 209). She is meant to serve as an intercessory figure for the reader of these devotional texts “by providing the eyes through which the devotee can witness Jesus’ suffering and death” (Reinburg 221-222). Mary’s provision of an emotional example is completely removed in the abridged Gospel Harmonies. In this way, the abridged Gospel Harmonies place a particular emphasis on Jesus’ suffering on the cross.

The Full John Account

Full John 18-19 versions of the Passion, such as with the Hargrett Hours, tend to tell a broader story than the Gospel Harmonies. John, as the foundational text for both the full accounts and the abridged Gospel Harmonies, was the choice text for the Books of Hours we analyzed. Of the twenty-eight manuscripts we analyzed (including the Hargrett Hours), sixteen contained the full John Gospel account.

In tradition, John the apostle, a follower of Jesus, was able to provide a firsthand account of Jesus’ life and death, so his words are invaluable and place users of Books of Hours at the closest point they can possibly be to the actual Passion. He takes on the role of a historian, and with this title, he becomes the voice that gives the most accurate account of the Passion. John also made numerous attempts to connect the events he witnessed to the Scripture that predates his work, becoming a witness to both the literal and spiritual events (Hazard 10-11). For these reasons, he appears to be the most popular author of the four evangelists for the Passion sequence in a Book of Hour.

We still get the gruesome details of Jesus’ suffering and death in the full Passion, but we are introduced to more of the emotional and mental trauma Jesus endured before and during his crucifixion. The full John 18-19 account includes meticulous detail and dialogue between the persons present in the Passion narrative, including Jesus, Simon Peter, Judas Iscariot, Pontius Pilate, Mary and Mary Magdalene, and even John himself, “the author of the Passion” and of the Book of Revelation in tradition (Weick 55, 104).

An important note before we move on: the beginning of John 18 and the end of John 19 in the Hargrett Hours are slightly different from the Vulgate. These are transition sentences that were often used in Book of Hours Gospel accounts. They were used to ease the reader in and out of Gospel text and rarely represent a substantial change to the Passion story.

John 18 details the events that occurred in the Garden of Gethsemane up until the Jews decide to free Barabbas, a robber, rather than Jesus, as a Passover tradition of the time. In between the Garden and Barabbas’ release, the former disciple, Judas Iscariot, betrays Jesus to the Pharisees for thirty pieces of silver, and they lead him to several judges and priests before ultimately giving him over to Pilate. Pilate debates with the Jews over Jesus’ sentence before interrogating Jesus about why the Jews are accusing him of proclaiming himself to be the Son of God and a king. Meanwhile, another disciple named Simon Peter watches nearby but denies his role as a follower of Christ when questioned.

Along the way between the Garden and the start of Jesus’ physical Passion, Jesus undergoes betrayal, rejection, and humiliation in very public settings, all indicating the emotional torture that he experiences. For users who wished to experience the affective impact of rejection and betrayal, the full John 18-19 account would take them step-by-step through the narrative of Jesus’ Passion.

John 18 sees Judas betray Jesus for money (John 18:2-7) and Simon Peter deny him three times (John 18:15-18, 25-27). His friends’ rejection of him, while not causing him physical harm, sets Jesus in a more emotionally isolated position than the abridged accounts, which remove them entirely. John 18 lingers on these emotional parts of the narrative and brings presence to persons who are removed from the abridged Gospel harmony accounts, making Jesus’ emotional turmoil more prominent. In the end, he finds himself standing alone in the face of violent adversity.

Pilate places Jesus on a stage before the Jewish people, and they choose a robber, Barabbas, to be released unto them at Passover instead (John 18:38-40), suggesting to Jesus that he is less than a common criminal. He receives the title “King of the Jews,” which mocks his sentiments to save them (despite his explanations that he is there to establish the Kingdom). He is isolated from the very people he is trying to save, and the Gospel presents Jesus as a solitary figure who experiences humiliation and shame.

Once Pilate interrogates Jesus again about his kingship and Jesus gives his famous answer (“regnum meum non est de mundo,” “My kingdom is not of this world” [John 18:36]), John 18 ends, and the more physical torment of Jesus takes place. Not once in John 18 is Jesus harmed physically in any way. John 19, however, opens with Pilate’s order that Jesus be flogged as the very first scene within the narrative, in stark and shocking contrast to the calm trials he faces before the judges and priests; Pilate’s soldiers mock him, dress him in purple robes, and place a crown of thorns on his head.

One last time does Pilate ask the Jews what they want because he does not find Jesus guilty (despite the flogging). He interrogates Jesus, who refuses to answer to Pilate’s liking. Once the Jews accuse Pilate (a Roman prefect) of being an enemy of Caesar (Tiberius by this time ~33 CE) by deciding to let Jesus go, he rescinds his statements and orders for Jesus’ crucifixion. Jesus’ physical Passion escalates here, when he carries the heavy wooden cross to Golgotha, a hill outside of Jerusalem. The soldiers divide his garments after they crucify him, and Mary and a few other followers make appearances before he dies.

Jesus, while hanging on the cross, asks for something to drink, and those present at the Crucifixion give him a sponge soaked in vinegar. Jesus gives his spirit to God (“consummatum est et inclinato capite tradidit spiritum,” “‘It is finished,’ and he bowed his head and gave up his spirit” [John 19:30]). The soldiers, rather than break his legs to quicken his death, see that he is dead and confirm it by piercing his side with a lance. Water and blood pour out. His followers, Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea, ask Pilate for Jesus’ body so they can bury him, and they seal him in the tomb.

Jesus’ actual physical torment is not long compared to the trial portions of John 18. We do see him flogged unnecessarily, but before he goes to Golgotha, he still undergoes the final verdict from Pilate. Pilate himself actually goes through some mental torment here himself, as the Jews manipulate him into his final decision to allow for the crucifixion. The trial portions break up the physical torture, but there are still some gory details, including the crown of thorns, the breaking of the prisoners’ legs (besides Jesus’), and the piercing of Jesus’ side.

The physical torment, unlike the abridged Gospel Harmonies, is not front-and-center in the full John 18-19 account. Rather, we see more details about the final decision, the casting of the lots for Jesus’ clothing, and the decisions made after Jesus’ death. There is more rejection on the part of the Jews, who do not want to be associated with Jesus and request that the sign above his name read that he declares himself the King of the Jews, not that he is the King of the Jews (John 19:19-22). The sign itself is written in Aramaic, Greek, and Latin, and is essentially designed to create a humiliating situation for Jesus by attracting a great audience. It tells all people in the area who can read any of the languages what he did.

Depicted as a man of humble means in the Gospels, Jesus does not have many possessions. To see his clothing taken from him and ripped to shreds (John 19:23-24) is emotionally painful because it is one of the few things he can declare his own. This event takes place while Jesus is on the cross, and rather than focus on his physical pain on the cross, the Gospel decides to draw attention to the emotional pain instead.

Figure 3: Baltimore, Walters Art Gallery MS W.197 Mary and John at the Foot of the Cross

The most gut-wrenching part of John 19 is when Mary watches her son suffer and die. Mary, John the evangelist, and other women are there to witness Jesus’ suffering. His great crowd of followers and disciples, however, are nowhere to be found. Mary and these few others are there for him, to support and comfort him in his dying moments and to see his mission fulfilled when so many others rejected him. As mentioned above, she and John the evangelist only appear in the full John 18-19 accounts and not in the abridged Gospel Harmonies. Mary’s inclusion provides an added emotional layer for the reader. With Jesus gone, she has no one else to take care of her, and Jesus’ last major act is to provide her with a trustworthy companion and son, John, to look after her in his place (John 19:26-28).

John’s physical inclusion in the full Passion account provides the user with a sense that he fulfilled his filial duty to Mary and his spiritual duty to Jesus. His presence surrounds the Book of Hours in these accounts because he wrote them and is within them. In this way, he provides comfort, both to Christ and Mary and to the user. Seeing him in the full account makes him, in a sense, more real. The Gospel Harmonies do not attribute the abridged accounts to one author, allowing for the different accounts to harmonize with the removal of John.

By including all of Jesus’ journey to the cross, manuscripts that include the full John 18-19 Passion account (such as the Hargrett Hours) demand more involvement of Book of Hours users by inviting them to participate in Jesus’ physical and emotional torment. Readers are positioned as witnesses along Jesus’ long walk from the Garden to Golgotha. They can identify with the fear of Simon Peter who denies Jesus to save himself, with the greed of Judas who sells Jesus for money, and with the sorrow of Mary when we realize what our sins have done.

Correlation between the Full John Accounts and Highly Personalized Owners

As a Book of Hours that includes the full John 18-19 passage, the Hargrett Hours is fairly typical. When we look closer at those manuscripts, though, we see that the Hargrett Hours belongs to a group of manuscripts whose texts were likely to have been specifically requested by their purchasers, and that it was likely meant for use by someone with a higher degree of biblical literacy than the average layperson.

Biblical literacy, in this context, refers to the amount of understanding one has of the religious content of the text. Literacy fell across a wide spectrum, ranging from those who knew a text through communal participation to those who could read the Latin and fully comprehend its meaning.

All Books of Hours were handmade, and there are varying degrees of personalization within the manuscripts. Books of Hours run the gamut from mass-produced (made in an assembly-line type process with no specific commissioner in mind) to deeply personalized (with the commissioner requesting even minute details). Out of the sixteen manuscripts we analyzed that include John 18-19, twelve are what we came to define as “highly personalized” books that have a high likelihood of being made to the user’s or commissioner’s particular specifications. The qualities we used to determine the degree of personalization are as follows:

- Personal inclusion of commissioner or commissioner’s family heraldry in illuminations.

- Personal inclusion of a family name or first name in the text (such as a name in a prayer).

- Knowledge that the named commissioner was a member of clergy, such as a bishop or cardinal.

- Knowledge that the commissioner or their family were historically devout.

- Inclusion of uncommon texts (such as the writings of a particular theologian).

- Inclusion of several uncommon saints in the calendar, suffrages, and/or prayers.

While we can’t know that a full John 18-19 account was chosen specifically for inclusion by a commissioner, these qualities mark a book as having been made with at least some thought to the commissioners’ personal requests. This research does not suggest that a Gospel harmony account means a Book of Hours was not highly personalized, but that the presence of a full John 18-19 passage has a high correlation with the book being highly personalized. Full John 18-19 accounts are longer than Gospel harmony Passions, which also supports the idea that having the full John 18-19 in a manuscript would be more common in a highly personalized manuscript.

We can’t say what a commissioner’s level of spiritual devotion would have been; however, ten of the fifteen full John 18-19 manuscripts have qualities that speak to a very high level of biblical literacy. These users would likely have been well acquainted with biblical teachings and would have been familiar with a larger body of biblical scholarship than the average layperson. They would have not just been able to read a Latin prayer aloud like many laypeople, but also could comprehend the meaning of Latin texts like the book of John.

For instance, two of these books (BnF Latin 1171 and BnF Latin 923) were commissioned by high-ranking clergy. Seven others (MS Richardson 9, De Villers 360, MS W.434, BnF Latin 757, MS W.211, MS W.411, and BnF MS 640) include uncommon texts, such as devotions to niche saints, extra-biblical texts by theologians, or the Passion of all four Gospels. One (MS W.178) even includes the commissioner’s name in a series of prayers, begging for the remission of sins. There is, therefore, a high correlation between books that include John 18-19 and commissioners who had a high level of theological knowledge and/or devotion. This does not mean the other five manuscripts were not personalized, just that their texts were fairly standard for Books of Hours.

It is important to remember that the Hargrett Hours is incomplete. Some of its pages have been removed, so we cannot know exactly what other texts or illuminations the original manuscript might have included. We know that the Hargrett Hours has a heavy emphasis on the Passion because it includes the Long Hours of the Passion, a series of Passion-focused prayers, and because its suffrages show a particular interest in saints with a personal connection to Christ. Eleven of the twelve apostles (Andrew excluded) appear in the suffrages, along with Saint Anne (Christ’s grandmother) and the Marys identified (in different Gospels) as having been at Christ’s crucifixion and/or resurrection: Mary the wife of Clopas, Mary Salome, Mary Jacobe, Mary Magdalene, and the Virgin Mary. The Hargrett Hours’ inclusion of the full John 18-19 passage falls in line with this Passion-heavy focus.

The Hargrett Hours stands out from all of these manuscripts in one primary way: the simplicity of its illustration. Books of Hours often include illustrations to help the less literate follow the text through images. There are, however, no extant full-page illuminations or heraldries and few ornate borders in the Hargrett Hours. Books that include full John 18-19 accounts were often highly personalized and made for the highly literate, but the Hargrett Hours’ relative lack of adornment further suggests it was made to be truly used as a text.

The choice of John 18-19 specifically speaks to a desire to study Christ’s Passion with all of its emotionally affecting moments intact. With a focus on Christ’s betrayal and shaming, the reader would have been encouraged to meditate on Christ’s emotional and not just physical suffering. It is likely the Hargrett Hours was commissioned for use by someone with devotional or theological intent and was not made with casual devotion in mind. This is in line with what the team researching the Hargrett Hours’ prayers has concluded: that the manuscript was likely used by someone in both a liturgical setting and for personal devotion. The Hargrett Hours was not for show or prestige, but for affective prayer and study.

Works Cited

Boulton, Maureen Barry McCann. Sacred Fictions of Medieval France: Narrative Theology in the Lives of Christ and the Virgin, 1150-1500. D.S. Brewer, Cambridge, 2015.

Hazard, Mark. The Literal Sense and the Gospel of John in Late Medieval Commentary and Literature, Routledge, 2002. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com.proxy-remote.galib.uga.edu/lib/ugalib/detail.action?docID=1581750.

Reinburg, Virginia. French Books of Hours: Making an Archive of Prayer, c.1400-1600. Cambridge UP, 2012.

Wieck, Roger. Time Sanctified: The Book of Hours in Medieval Art and Life. George Braziller, 2001.